Seeing and Seeing Again in Cali, Colombia

An autoethnography by Jimmy Hallyburton

Jimmy Hallyburton is a student in Gonzaga’s Master’s of Organization and Global Leadership program. The following is an autoethnography (Auto: self. Ethnography: a qualitative and immersive reflection related to culture, behavior, and community). The account below describes a 2-week immersive experience in Cali, Colombia, where he studied the role of art, creativity, and cultural cartography in building peace and community.

Seeing and Seeing Again in Cali, Colombia

A Lens

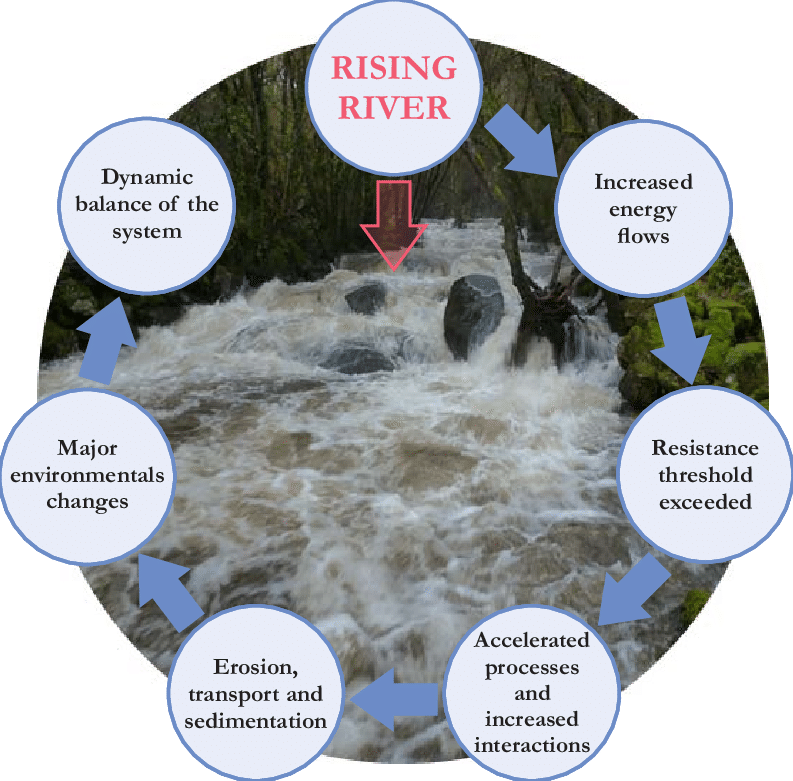

There is a quote from the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.” At risk of ruining the opportunity to dwell on how that quote might have a unique meaning and application for each and every individual, I’ll explain the metaphor from my own lens and experience.

García, Horacio & Ollero, Alfredo. (2016). An Introduction to Flood Risk and Management.

The world and the spaces and places embedded within it are not stationary objects. Like a river in different seasons, they can have moments of peace and moments of extreme turbulence. At high water flows, a massive boulder can slowly dislodge from the bank, roll into the center of the river, and forever change the flow and dynamic of everything below it. Extreme rain can create mudslides that change the water itself. Extreme drought can transform the river into a stream. The river, from its content to its structure, is never the same river, and no amount of human or environmental intervention, or lack thereof, could prevent its ever-changing nature.

In the same capacity, humans, no matter how hard we might try, cannot remain the same. Beyond the physical and cognitive aging process, we are shaped by our life experiences and emergent truths. Our perspectives change, sometimes gradually and sometimes rapidly, from our interactions with others and the environment that we live in. I would argue that exposure to unfamiliar and sometimes uncomfortable experiences has an exponential ability to rapidly shift the way we see the world, each other, and ourselves, as well as our actions—good or bad. Our bodies, our assumptions, and our perceptions do not and cannot stay the same. We cannot stand in the same river twice and are therefore challenged to adopt the Ignatius philosophy of “seeing and seeing again.”

While preparing for a 2-week immersion in Cali, Colombia, this quote and philosophy were often on my mind. As I researched the content and context of the communities I would be engaging in, I knew my capacity to truly understand and prepare for the experience ahead was limited. I knew any assumptions and perspectives formed outside of the community would be challenged upon arrival and broadened with every real interaction. And, even once embedded within the community, I knew my scope and understanding would be limited by my own cultural biases—what is “good” and what is “bad”— and by the partial view I would be exposed to. I challenged myself to recognize what I would be seeing and what I might not be seeing within my limited exposure in a complex and dynamic community. In this capacity, I was looking to expand my own truth, to seek out the truths of others, and get a glimpse of a greater truth that, although ever-changing and likely incomplete, could result in shared growth.

Through this lens of dynamic growth and philosophy of seeing and seeing again, the immersive and intercultural autoethnography below seeks to address a greater understanding of how the arts and creativity can be used in conflict transformation, to build peace, and to shape leadership.

Welcome to SiloÉ

Siloé neighborhood in Cali, Colombia. Taken from the Mio Cablé

On a hillside along the western edge of Cali, Colombia, exists a small but vibrant neighborhood called Siloé. Siloé has a complex history deeply impacted by structural, direct, and other forms of violence. Many people living in more affluent areas of Cali still view the hillside area as dangerous, and very few, some living less than a mile away, have traveled into the neighborhood. As recent as 2021, violent protests, shootings, murders, gang activity, and other forms of violence made Siloé one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Cali.

Efforts driven from within the neighborhood, as well as public investment and institutional support from universities, have helped address some of the most visible forms of violence and conflict in Siloé. Formal and informal organizations have emerged to help build peace, establish cultural identity and place, and establish infrastructure to promote economic prosperity. Despite these efforts and measurable improvements, conflict continues to exist.

In July 2025, a cohort of Gonzaga grad and undergrad students arrived in Cali, Colombia, to learn about its history of violence while immersing themselves in neighborhoods and organizations seeking to build peace through various forms of art. I was among them, and I was assigned to Arté Y Vida, an organization involved in peace-building through circus arts near the top of Siloé

I knew about Siloé’s history of violence when I climbed into the back of a guala (see photo and video below) and began heading up the hill. On this ride, I sat in the very back, a premium spot as it offers the best view and the only opportunity to extend your legs. This is a fun and novel experience for any outsider, but a normal form of commuting for many locals. As we traveled up the hill, we couldn’t help getting caught up in the vibrant murals painted on buildings, the smell of food cooking, the cute animals wandering the streets or barking from second-story windows, the motorcycles with smiling kids on the back, and all the people who seemed full of life. It was easy to look past buildings with leaky roofs, streets unaccommodating for anyone with mobility challenges, and living conditions/infrastructure/utilities that showcased the high level of poverty. It was often easy for the visible good to overshadow the challenges hidden in plain sight.

As we neared the top, the sound of drums surrounded our vehicle, and I don’t think anyone was prepared for what we would experience next (see video 0:45). I stepped out of the back of the guala to find a drumline of teenagers with young children covered in face paint and dancing on stilts behind them. These were the kids of Arté Y Vida, the kids I would spend the next two weeks with. With minimal Spanish-speaking skills, I immediately approached the kids and did my best to communicate my appreciation and awe of their stilt walking skills. We bonded immediately, and I was instantly reminded of the arts' ability to break down barriers. Soon, the kids were guiding us, still on their stilts, up the steep roads, through staircase-constructed alleyways, and to the very top of Siloé.

I’ve spent most of my adult life engaged in the creative community. As the founder and 16-year Executive Director of the Boise Bicycle Project and three-term member of the Boise City Council, I’ve seen and advocated for the power of art, music, bicycles, and shared cultural experiences to bridge boundaries and bring people together. Even as a lifelong advocate for the arts, I was skeptical of its lasting ability to address widespread and deeply ingrained structural violence in an area like Cali, or the United States for that matter. In Tiffany Fairey’s 2017 report, The Arts in Peace-building and Reconciliation: Mapping Practice, she states, “Historically, advocates have tended to romanticise and be over optimistic about the effects of arts work in post conflict societies. Statements about the transformative power and significance of the arts have been made without qualification or clarification." To me, it was never a question of art’s ability to create change at a micro or even meso-level; I firmly believed it could. It was a question of whether it could create change at the systematic and structural scale—macro-level—needed to bring peace to a city like Cali and a neighborhood like Siloé. For the record, I’ve never been deterred by my own skepticism. Quite the opposite, it often leads to extreme, bordering on excessive, curiosity. And standing on the top of Siloé, surrounded by kids on stilts and the pounding of drums, I was curious.

Immersion

Day 1

As a mid-career grad student simultaneously serving on the Boise City Council and teaching at a community college, I’m accustomed to a fairly tight schedule and well-planned-out agenda. I came to Cali with no such expectations and ready to “go with the flow.” My experience traveling around the world and engaging in intercultural experiences has taught me to check my expectations at the door and dive deeply into the beauty of the stretch zone. In Intercultural Communication, Globalization and Social Justice, Kathryn Sorrells (2022) expands on this process as she describes “engaging in intercultural praxis,” a methodology that includes Inquiry, Framing, Positioning, Dialogue, Reflection, and Action. All of which require a suspension of judgment and the binary perception of what is “right” and what is “wrong” (pp. 266-269)

Thank God I came in ready to abandon my well-structured frame of reference for what an agenda and defined project plan should or shouldn’t look like, because we, the four students assigned to Arté Y Vida, spent a week and a half engaged in deeply vulnerable and scaffolded exercises without knowing where we were headed. On our final day of work, we were introduced to what would become our final project. Days later, we would present it to our fellow students and faculty leaders at one of Cali’s most prestigious universities. On the morning of the final day at Arté Y Vida, we stared at two blank pieces of poster paper, hung on the wall with masking tape. We did not know what would happen next. But that’s jumping ahead.

“The entry point of inquiry requires that we suspend our judgements about others, loosen our posture of defensiveness, and have a willingness to know the experience of the other,” Sorrells (2022, p. 266).

The initial guala ride up to Siloé and welcoming celebration hosted by the kids from Arté Y Vida was our introduction to the community and organization. We did not realize, until our final day at Arté Y Vida, that it was a central part of our project. Our second guala ride up to Siloé failed miserably. Either our guala driver got lost, or he felt uncomfortable going into the neighborhood and got lost on purpose. We were forced to abandon the guala and take the Mio Cablé, an elevated gondola-form of public transport that takes you from the bottom of the hill to the top. This is an example of public investment designed to aid in transportation for the residents of Siloé. It is also, intentionally or unintentionally, a step toward addressing structural violence. Looking back, our failed guala ride was an incredible gift. It allowed us to see Siloé from a broader geographical and cultural lens.

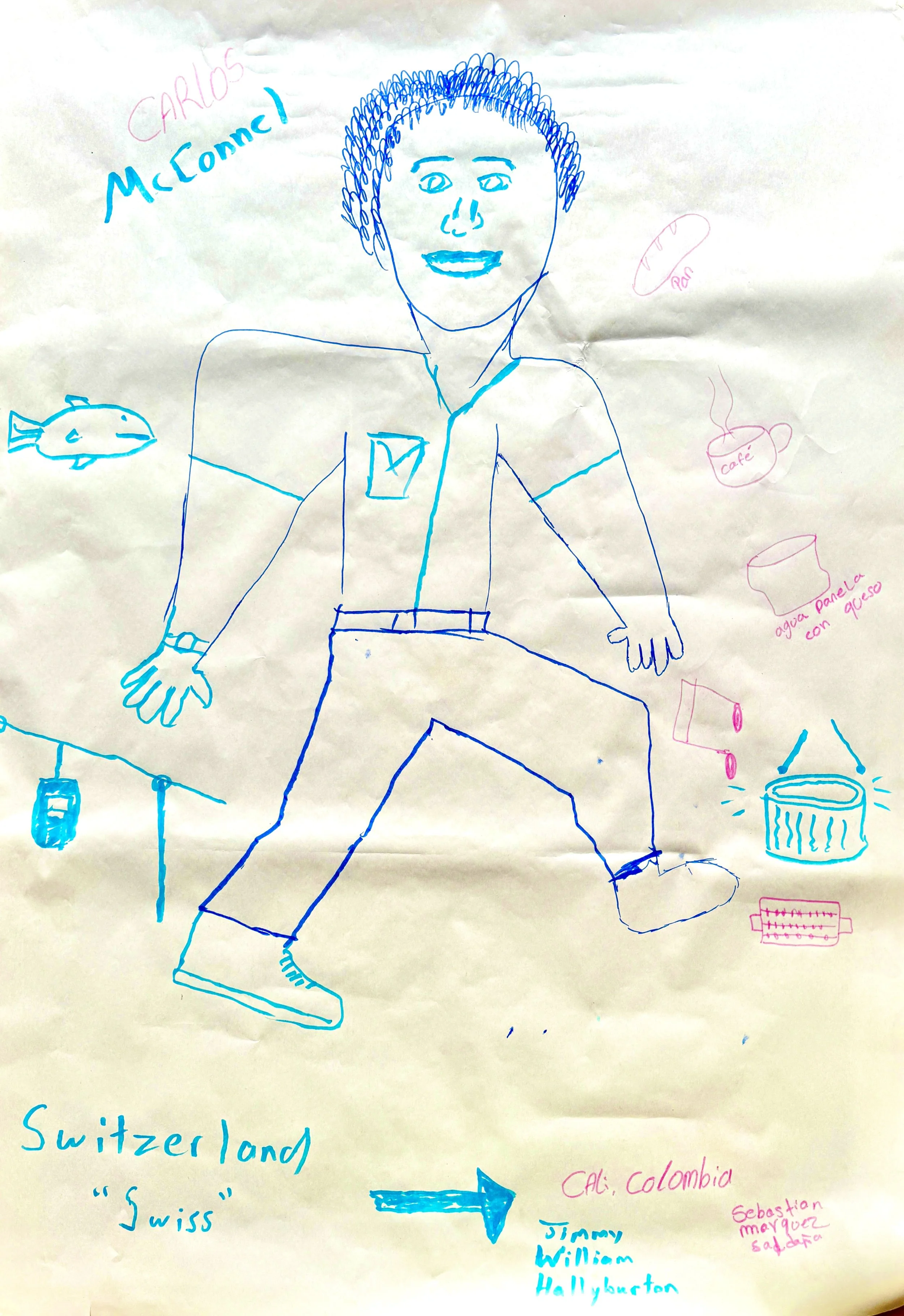

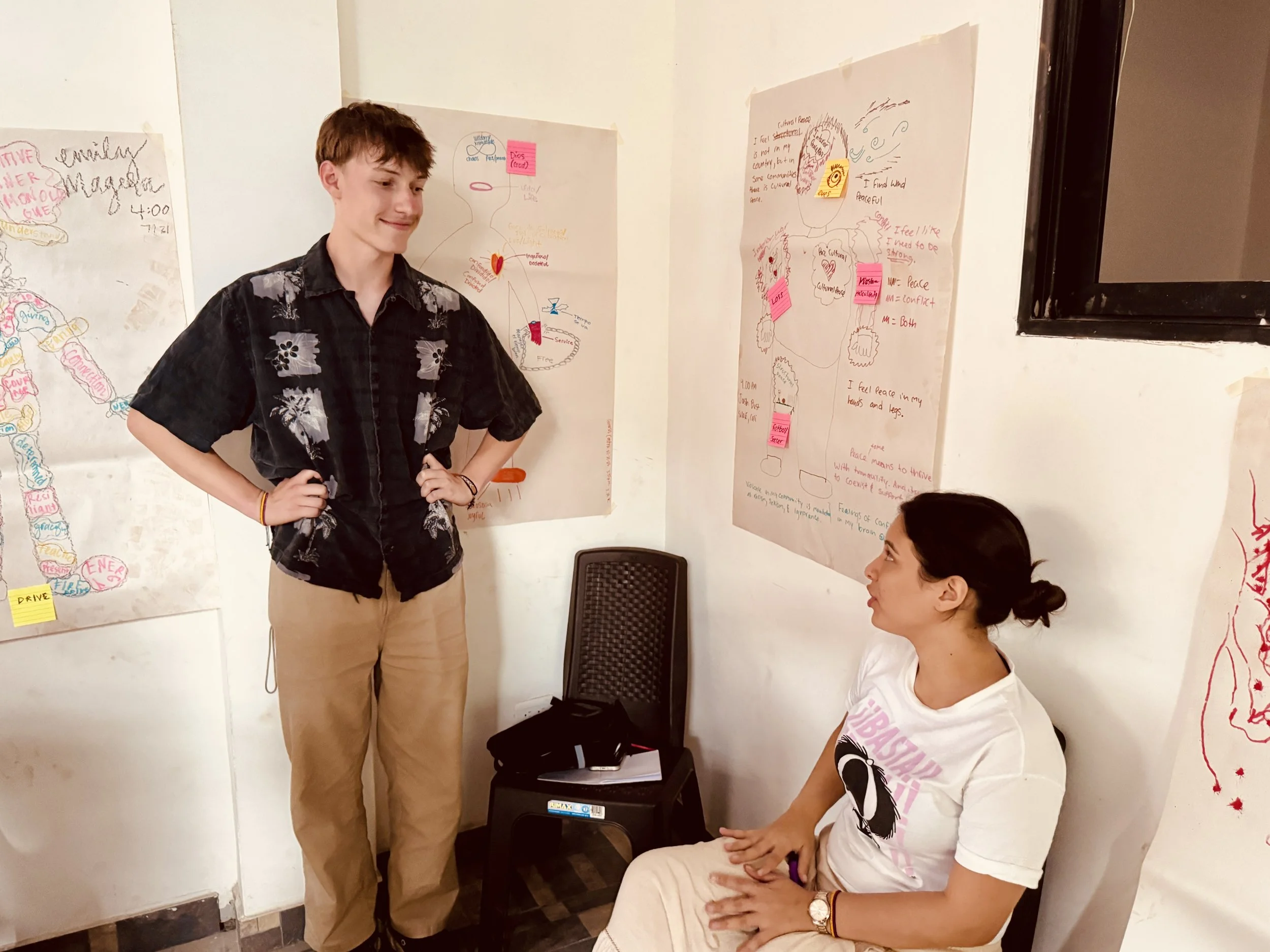

When we finally arrived at the Arté Y Vida headquarters, we were met by Maria, one of the Arté Y Vida leaders and the architect guiding our experience, and we began to engage in a cultural cartography exercise (a method of mapping cultural landscapes to represent the human experience within a specific place) without fully realizing it. I was paired with Sebastian, one of the drum-playing teenagers from our initial visit to Siloé, and we were instructed to draw a fictional character and create their backstory. To be honest, I was confused about the instructions, as many of the details were lost in translation. I had to trust Sebastian to help guide me through the process. This might have been an intentional step in leveling the privileged positioning between the Gonzaga students and the kids at Arté Y Vida. It’s hard to say, but the impact was the same. And so, a non-Spanish-speaking city council member from Boise, Idaho, began to create a made-up person with a non-English-speaking local teenager from one of Cali’s most historically violent neighborhoods. I should mention that throughout the exercise, Arté Y Vida’s building was under construction, and we were covered in dust; we could barely hear each other over the hammers banging on the wall. This was day one of our project.

As we said goodbye and took the Mio Cablé back to our lodging, a metaphor for imperfect peace began shaping in my mind, and a foreshadowing of the challenging yet overcomeable obstacles ahead emerged. In The Little Book of Conflict Transformations, John Paul Lederach (2003) states, “Conflicts are natural in social relations and play an essential part in social change. Peace and reconciliation do not involve the elimination or absence of conflicts, but their positive and peaceful transformation.” If any expectation for a smooth and predictable experience had existed within me, consciously or unconsciously, it had now vanished. Vulnerable participatory action and dialogue in the face of inevitable conflict appeared to be the path we were headed down.

Day 2

We departed via guala for our next experience at Arté Y Vida. This driver was from the neighborhood, and we couldn’t cover a single block without people yelling his name and giving a wave. Halfway up the hillside, a young man ran beside us, jumped onto the rear bumper, yelled to the driver to see where we were headed, and jumped off the next time we slowed down. This was acceptable behavior, and why not? We were going up.

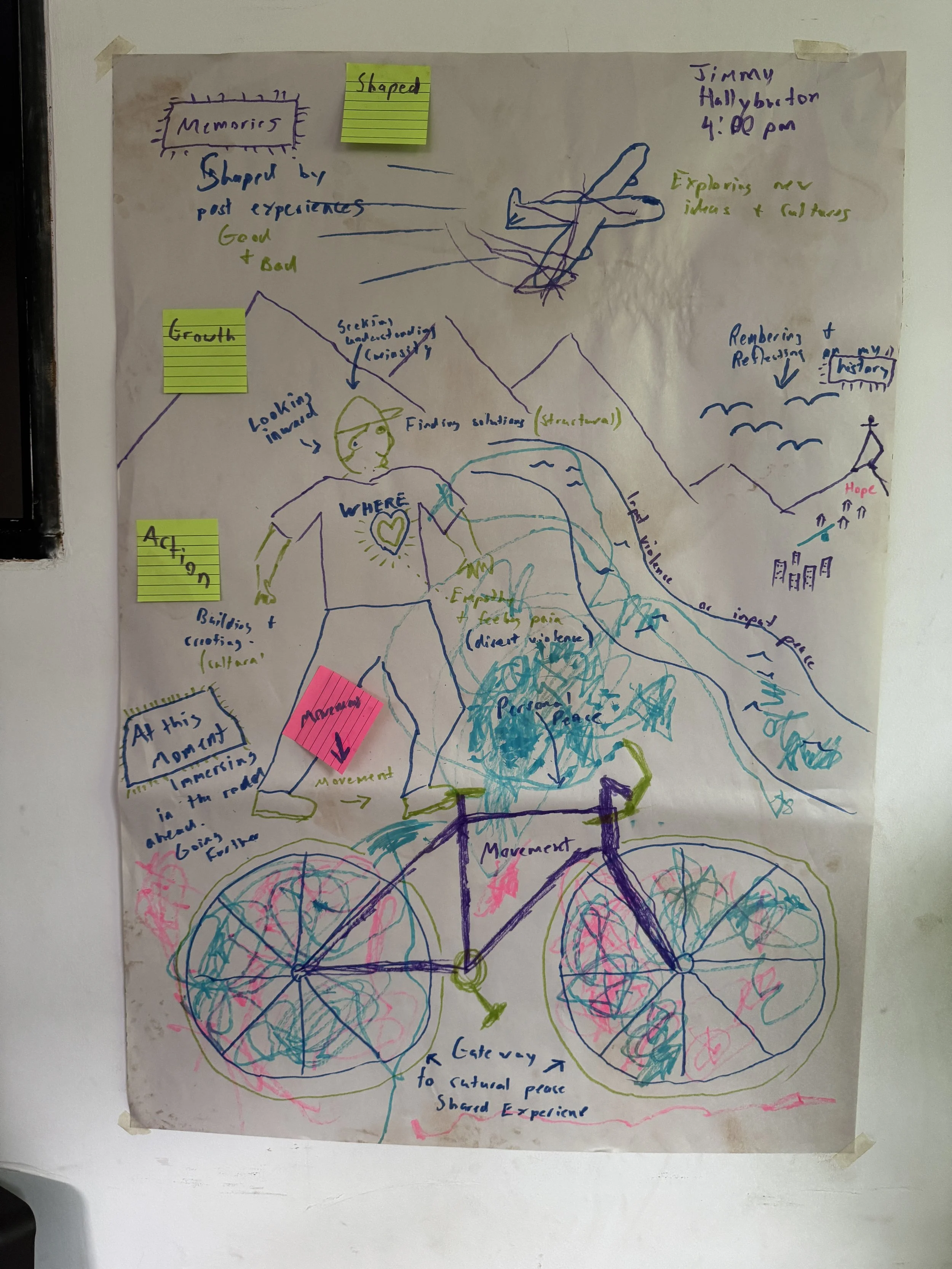

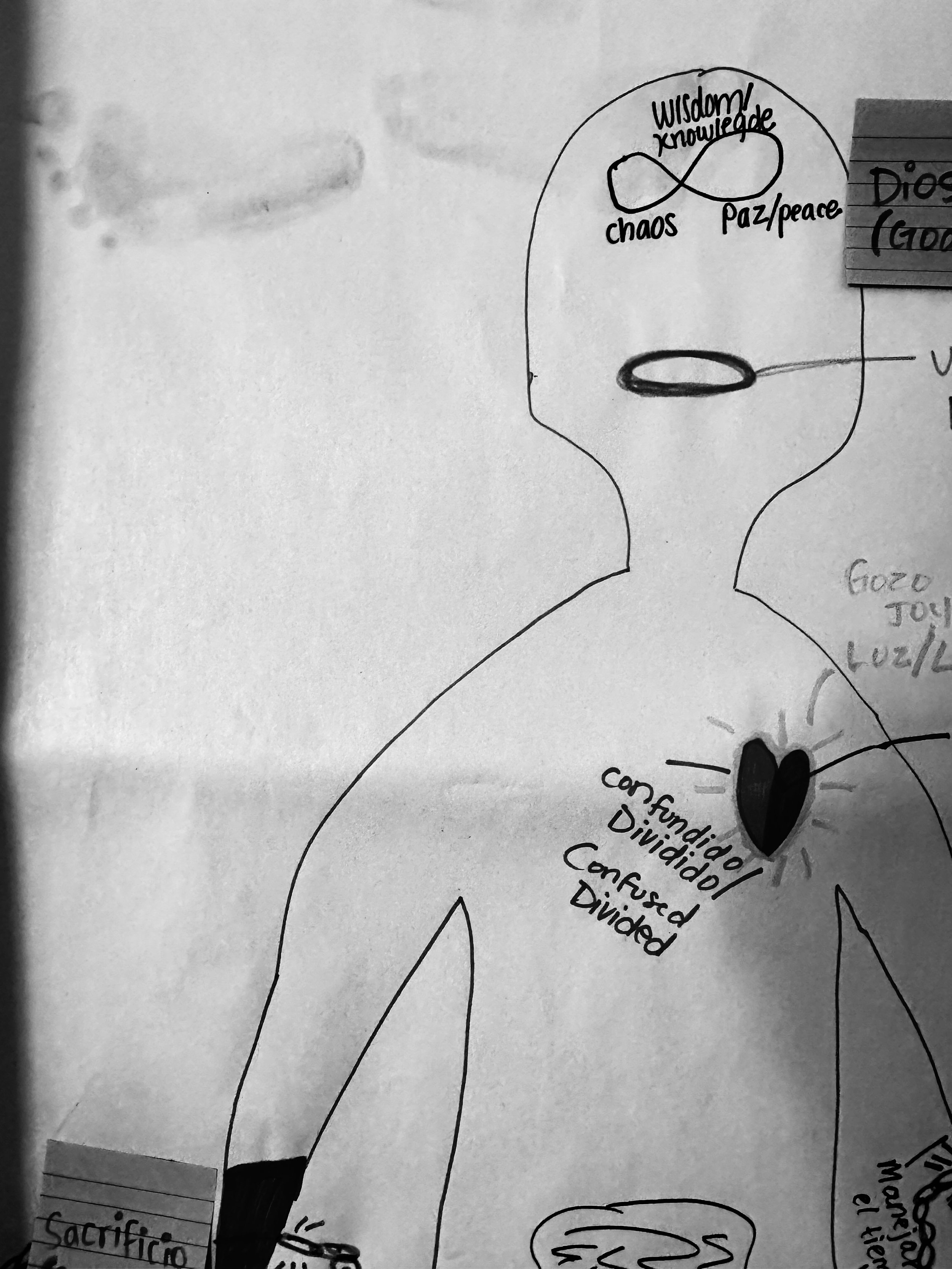

Once we arrived, we put our fictional characters aside. Maria instructed us to begin drawing personal body cartographies, drawing ourselves and mapping out the areas where we felt different forms of joy and conflict. Other than maybe noticing my elevated heart rate during times of stress, I had never put a lot of thought into where and how I felt different emotions in my body or through the objects I interact with. I hadn’t thought about feeling “purpose” through my feet as I move, sometimes slowly and sometimes swiftly, throughout the world. I hadn’t noticed that anxiety almost always originated in my shoulders, and hope through my eyes, peace through my hands as I fix things once broken, and confusion in the front of my head, yet reflection in the back. I had never recognized that empathy and pain reside in my heart, but rarely love and joy. Actually, I didn’t list love and joy anywhere on my body cartography.

I completed my drawing and began to observe and take photos of the other students. This task was welcomingly interrupted by a toddler, whom I believe was the daughter of one of the Arté Y Vida teenagers, still working on their drawing. The toddler was clearly jealous of the activity and wanted to be included. So I invited her to color with me on my “completed” drawing. As she brought color and life into my body cartography, I also realized she was bringing the love and joy that I had been missing. With her assistance, my drawing and actuality became “more complete.” Both a metaphor and a reality exist in that statement.

In Miguel Barreto Henriques’s article, A Reconciliation Laboratory? Theatre among Former Enemies in Colombia (2022), he states, “To a large extent, the transformative power of art lies in its ability to work on the emotional dimension.” Reflecting on the moment described above, I would add that the transformative power of art lies in its ability to create connection through the emotional dimension, even in the presence of difference. Does transformation occur through art when it helps us see and understand the other? Or, does it happen when art helps us see ourselves within the other? I was coming to see a difference between the two.

Day 3

“Art and peace are both located in the tension between emotions and intellect. Life unites what concepts and dualisms keep apart. And art, like peace, has to overcome such false dichotomies by speaking both to the heart and to the brain, to the compassion of the heart and the constructions of the brain,” Johan Galtung (2015).

On day 3 at Arté Y Vida, we began to share our body cartographies with the rest of the group, searching for differences and similarities, and, in the end, building mutual understanding across cultural divides. It was a vulnerable experience, and there were tears as we challenged the concept of dualism between our minds and our bodies, as well as the individual and the collective. I started the group off with the story of how my cartography became more complete through the human connection with the toddler. I showcased my dependency on finding love and joy through interaction with others. Each person’s cartography and share-out was unique. Many of the feelings–love, conflict, peace, stress–were universal, but the locations felt in the body and the reasoning behind the location were different.

As stated earlier, I am a firm believer that people are a result of their life’s experiences. Every experience, good or bad, has played a role in shaping who we are. And, that means who we are today does not necessarily mean we will be the same person tomorrow. Our access to a diversity of experiences, viewpoints, and interactions, or lack thereof, continues to shape us moment by moment. My body cartography “completed” at Arté Y Vida will, hopefully, evolve over time. The reflective action of creating and dialogical action of sharing and receiving our human experiences in an intercultural setting opened the door for me to see myself within the other. I had never experienced the structural violence common to the students of Arté Y Vida, and they had never experienced the weight and responsibility of serving in an elected position. However, we had all felt love, fear, stress, peace, and violence within our bodies, and that connection created opportunity for a common path forward. As Fairey (2017) puts it, “Art projects that pursue dialogue acknowledge the existence of multiple truths (rather than advocating a singular truth) and seek to enable a dialogue between these different truths.” This is a pathway toward imperfect peace.

Day 4

It was our final day at Arté Y Vida. One last guala ride to the top of Siloé. Today we would begin the final project, not knowing what it would it would look like, and unaware that we had already begun. Maria started the day with the Arté Y Vida students teaching us how to play the drums. Even the youngest kids were better than we were, holding power over mid-career grad students. This exercise helped level the positioning within the group and highlighted that we all have something the share and something to learn. Up to this point, most of the creative exercises had focused on inward self-exploration combined with vulnerable sharing–trust building–amongst the Gonzaga and Arté Vida students. The drumming exercise helped shift the focus of our individual humanity to our collective strength. It set the stage for the transformation to come and established shared roles of leadership and responsibility for everyone in the room.

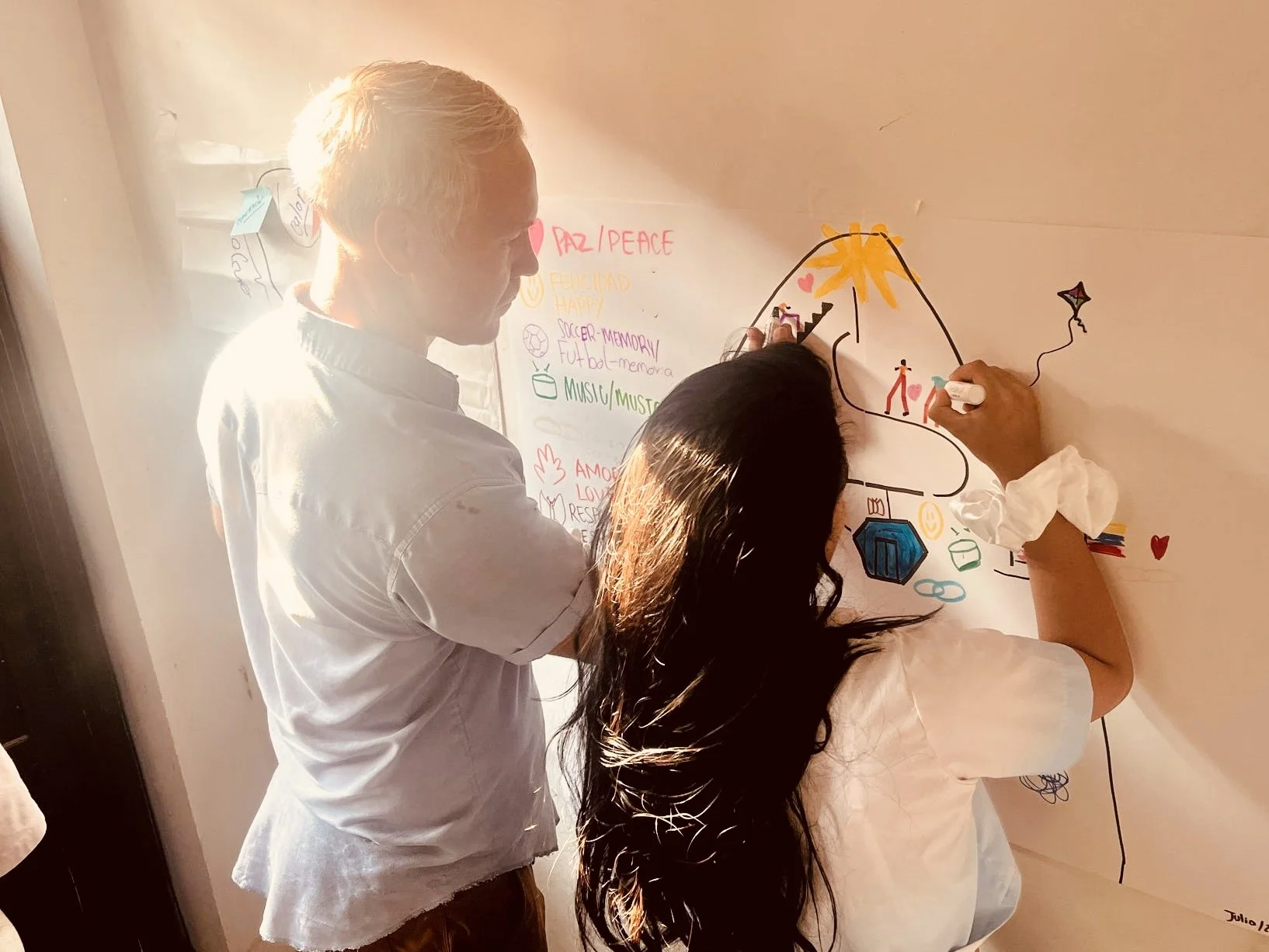

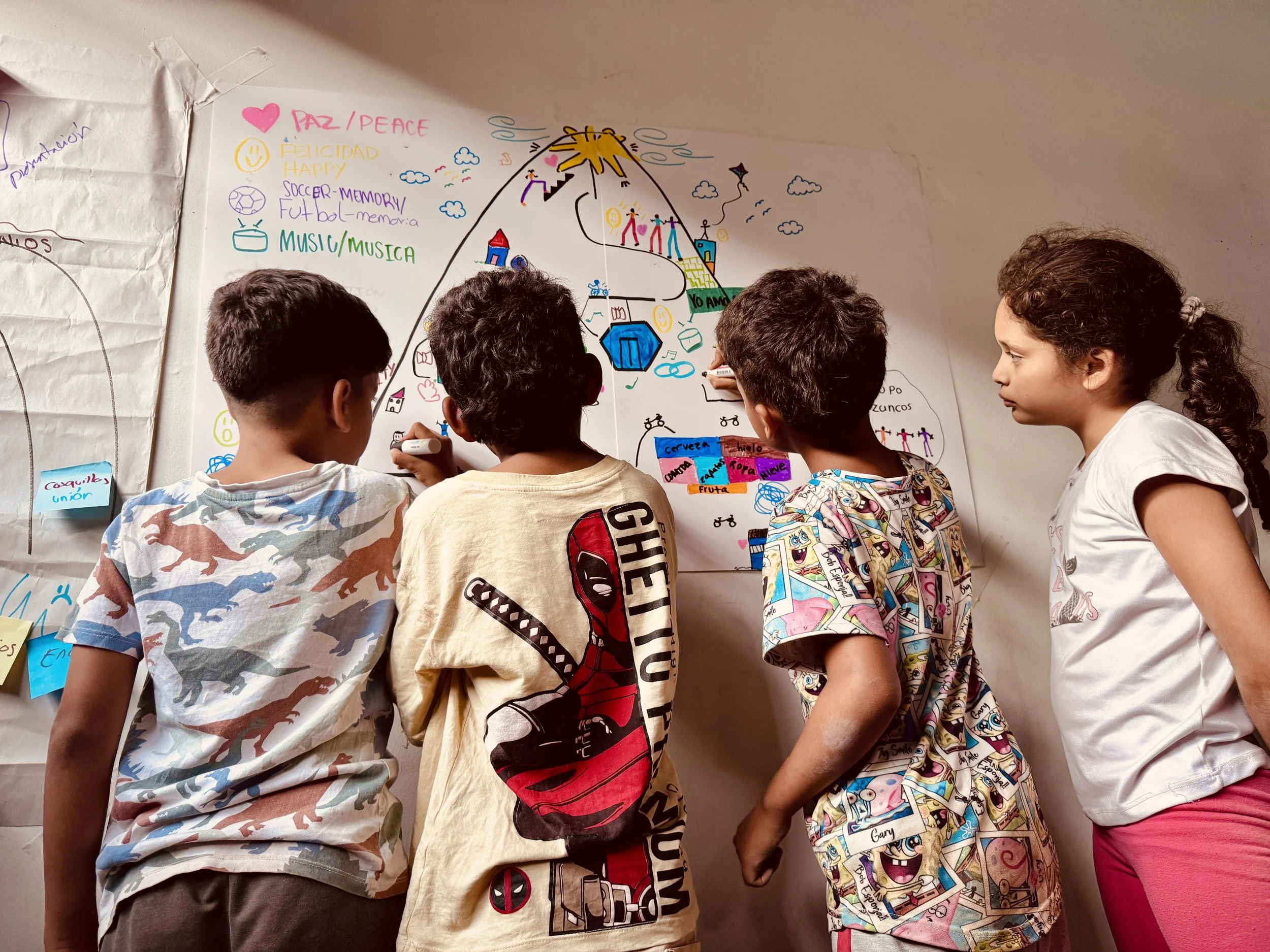

I stared at the two blank pieces of poster paper taped together on the dusty wall of Arté Y Vida, wondering what would happen next. Then Maria drew one large hump across the two, representing the hilltop neighborhood of Siloé. Our next step was to collectively draw the places in the community that represented various feelings of peace and conflict. She gave us every color of marker and finger paints imaginable and instructed us to start mapping. In our body cartography, we mapped the feelings within our body; now we were shifting to cultural cartography and mapping our personal and shared humanity within a community. In some ways, this made me feel very uncomfortable. I questioned my role in mapping out a community I had experienced for less than two weeks. I did not want to intrude on the truths of those in the community. And then I realized I was missing the point.

“It is when artists work in collaboration with others – youth workers, community leaders, educators, NGOs, peace activists, human rights groups, academics and institutions – that skills can combine, complement each other and impact can be maximized,” Fairey (2017).

In the days leading up to our final project, Maria had helped bring trust and individual truths into the group. She had also allowed us to recognize the shared value of each other's strengths and skills. The final project was an opportunity for the truths of existing community members to exist alongside and merge with the truths of outsiders new to the community. It was an opportunity for everyone involved to see and see again.

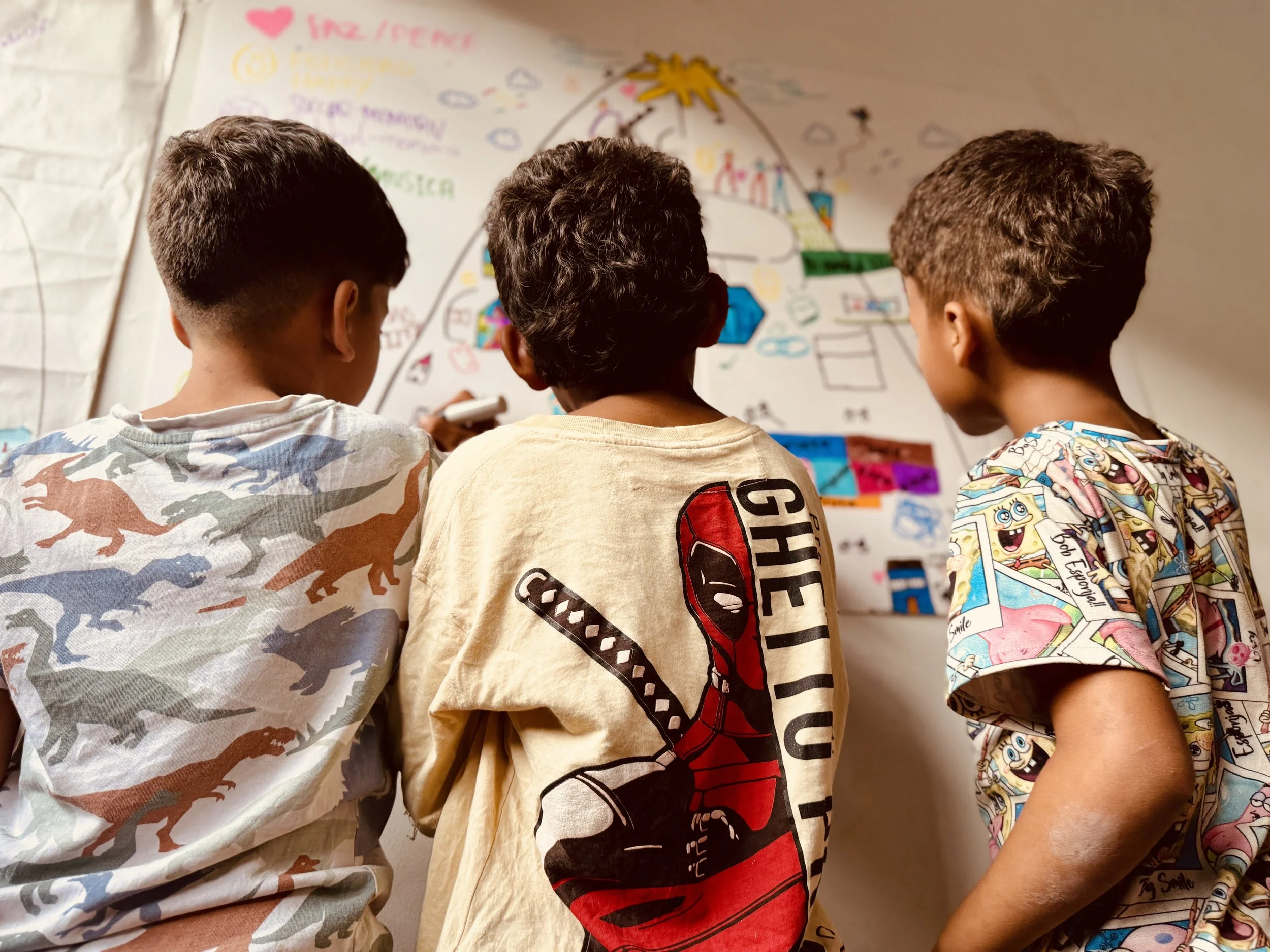

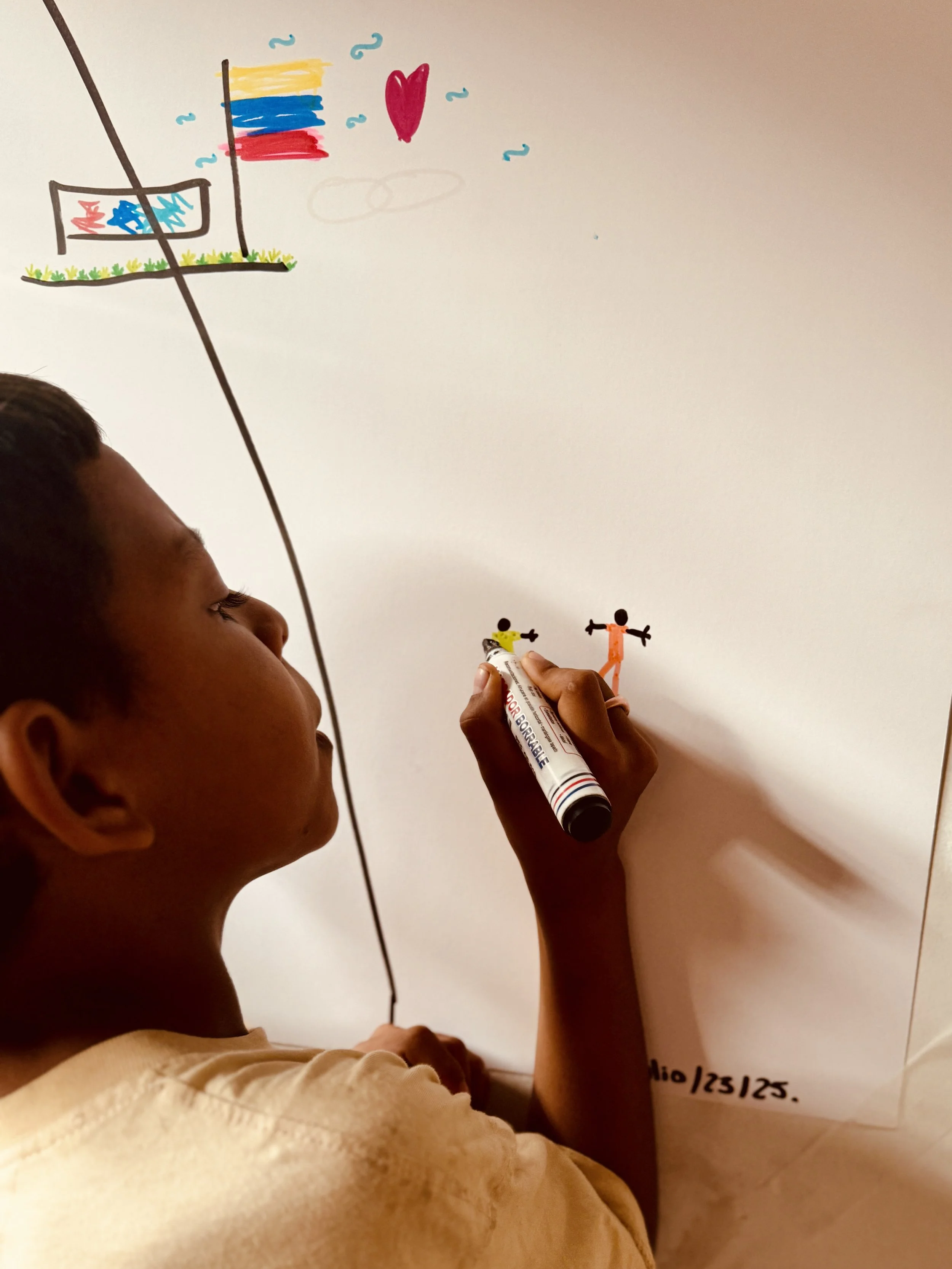

The Gonzaga students and Arté Y Vida teenagers began to populate the map. The Mio Cablé was drawn down the center. For some, it represented peaceful tranquility; for others, it represented strength and new possibilities. Teenagers drew their houses and pets, representing love and safety. Gonzaga students drew buildings with murals that represented hope. At first, it was difficult to get the younger Arté Y Vida students, the littles, to participate. The hillside was not yet familiar, and they couldn’t see themselves in it. Maria put another piece of paper on the floor and had the littles draw themselves instead.

As the hillside became more and more detailed with important cultural structures, the littles finished their own drawings, and they began to recognize what was being created on the wall. They began to see parts that were missing and were soon crowded around the poster board, adding themselves, often on stilts, to all of the places that were important to them. They added their houses, trees, soccer fields, and other places the Gonzaga students didn’t know existed. One of them colored in a building outline that I had drawn. Clearly, the vibrant colors of the neighborhood had special meaning to them. Once again, something I had “completed” became more complete. My truth, with the help of an other, had become a shared truth and a greater truth.

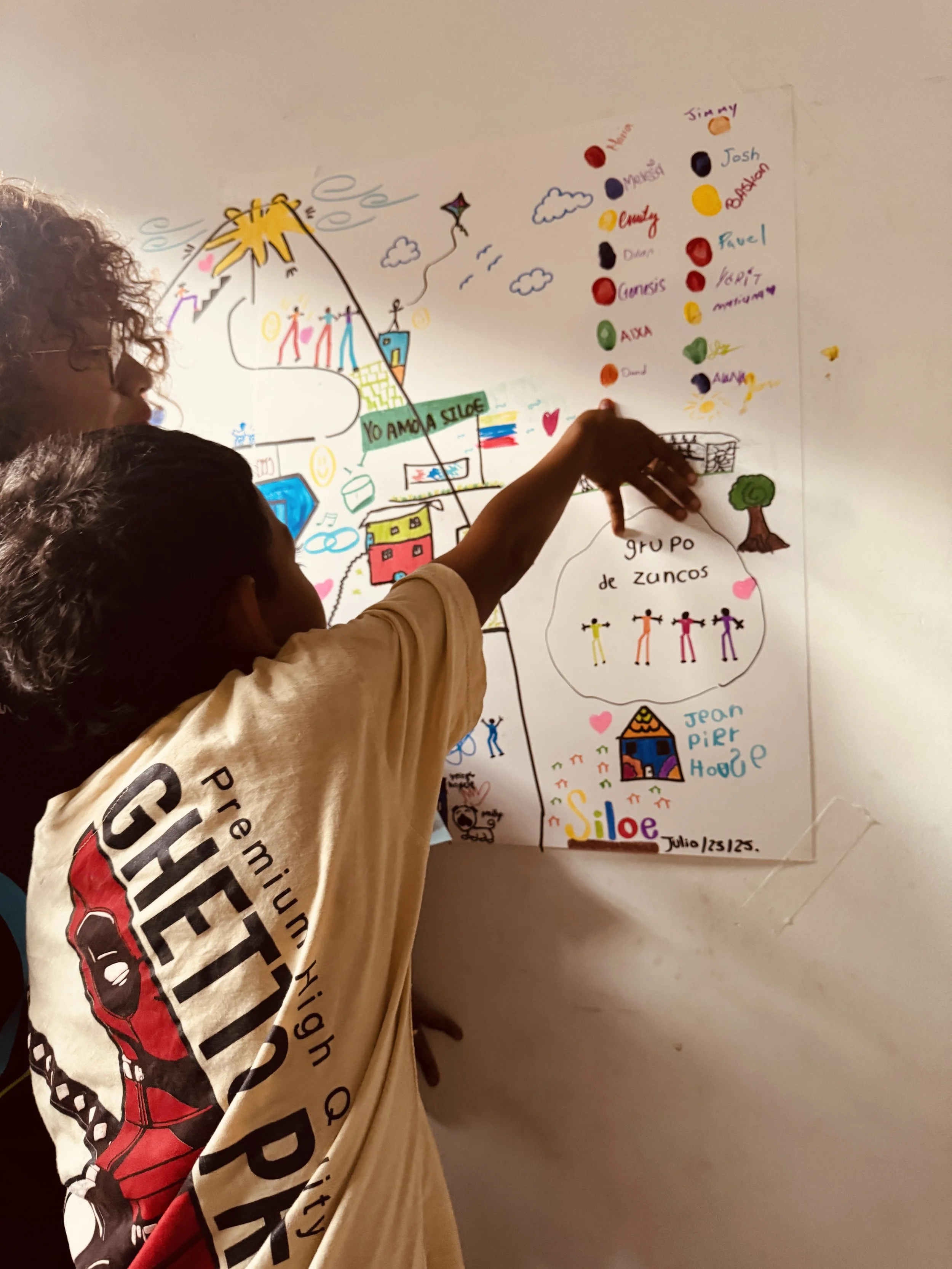

At first glance of the final drawing, it appeared pretty simple. In reality, it was an incredibly complex, multicultural, and multigenerational snapshot of the Siloé community. It articulated symbols of peace, symbols of violence, symbols of shared meaning, and symbols capturing multiple truths. Everyone saw themselves and the collective represented in the community. Before we headed down the hill for the final time, Maria had one more task for everyone to complete. One at a time, each of us dipped our thumbs into a different color of paint, pressed our thumbprints onto the top corner of the map, and signed our name. As the artists, this was our claim to the work we had created. As participants in peace-building through cartography, this was also a symbol of our collective ownership of our journey and collective responsibility for preserving and building peace within the community.

Transformation, Peace-building, and Leadership

“The arts are transformative: they can change how people look at themselves, their situations, and at each other; they make meaning and give us new stories and ways to understand experience. The transformative impact of the arts is complex, unpredictable, non-linear, and highly subjective, making it hard to quantify,” Fairey (2017).

To engage in the arts calls for a willingness to explore the unknown. It means searching for meaning in undefined areas and creating connections across boundaries that help us imagine better outcomes. To engage in research often means approaching new information and individual outcomes with curious skepticism. This is the dichotomy of the heart and the mind, and perhaps leadership is the bridge between the two.

The peace-building exercise I engaged in at Arté Y Vida was, in no doubt, transformative for all of those involved. I believe everyone who participated left the experience with a new understanding of themselves, each other, and the surrounding community. The lasting impact related to building peace in the broader context may be limited and undefined, but the lens through which each participant–assigned and emergent leaders–viewed humanity was altered. There will be cascading impact as these leaders continue to engage in community-building. I would argue that the tangible impact of something as simple as a brightly painted building and the regular artistic performances in Siloé was qualitatively defined through the shared perception of outsiders and community members. I would also argue that the Mio Cablé and use of gualas for public transportation showed meaningful progress in addressing structural violence, but also relied on a cultural component to be fully effective. This cultural component should not be ignored as new infrastructure is evaluated.

A question remains whether the cultural cartography exercise could be scaled or adapted to create broader structural change. I found myself asking if this could be replicated with higher-level decision makers, organizational leaders, and other community leaders to have a larger and lasting impact. I believe it could. As a leader in my own community, I see the exercise as a tool that could be used in different settings with higher stakes to help individuals see themselves, each other, and the collective, and see again. I also believe something magical happened on the hillside of Siloé that is hard to capture. Perhaps that is the risk and the strength of the arts’ role in creating transformational change. It is unpredictable and undefined. And perhaps the call to leadership is to build the adaptive strength, showcased by Maria at Arté Y Vida, to navigate and accept this risk.

References

Fairey, T. (2017). The Arts in Peace-building and Reconciliation: Mapping Practice.

Galtung, J. (2015) “Peace, Music and the Arts: In search of interconnections” in Urbain, Olivier (ed.) Music and Conflict Transformation: Harmonies and Dissonances in Geopolitics, Londres: Tauris, pp 53-60

Henriques, Miguel Barreto (2022). A Reconciliation Laboratory? Journal for Peace and Justice Studies 31(2):3-20.

Lederach, J. P. (2003) The Little Book of Conflict Transformations, Good Books.

Sorrells, Kathryn (2022) Intercultural Communication: Globalization and Social Justice (Third Edition). Sage Publications.